The conversation usually goes something like this:

They look puzzled. “What is shibori?”

I try. A Japanese term. For a range of techniques that involve manipulating the cloth and then binding or stitching it to create a resist before dyeing.

…

I give in. “Like tie-dye”.

Light dawns.

Techniques involving bound or tied resists are found in many parts of the world, including India, West Africa, Indonesia, Central Asia, South America. In Japan, they date back to at least the 8th century and probably beyond. Sometime in the 14th century, Japanese dyers also worked out how to make stitched resists and how to protect selected areas of the cloth from the dye – opening up a whole new range of pattern-making possibilities.

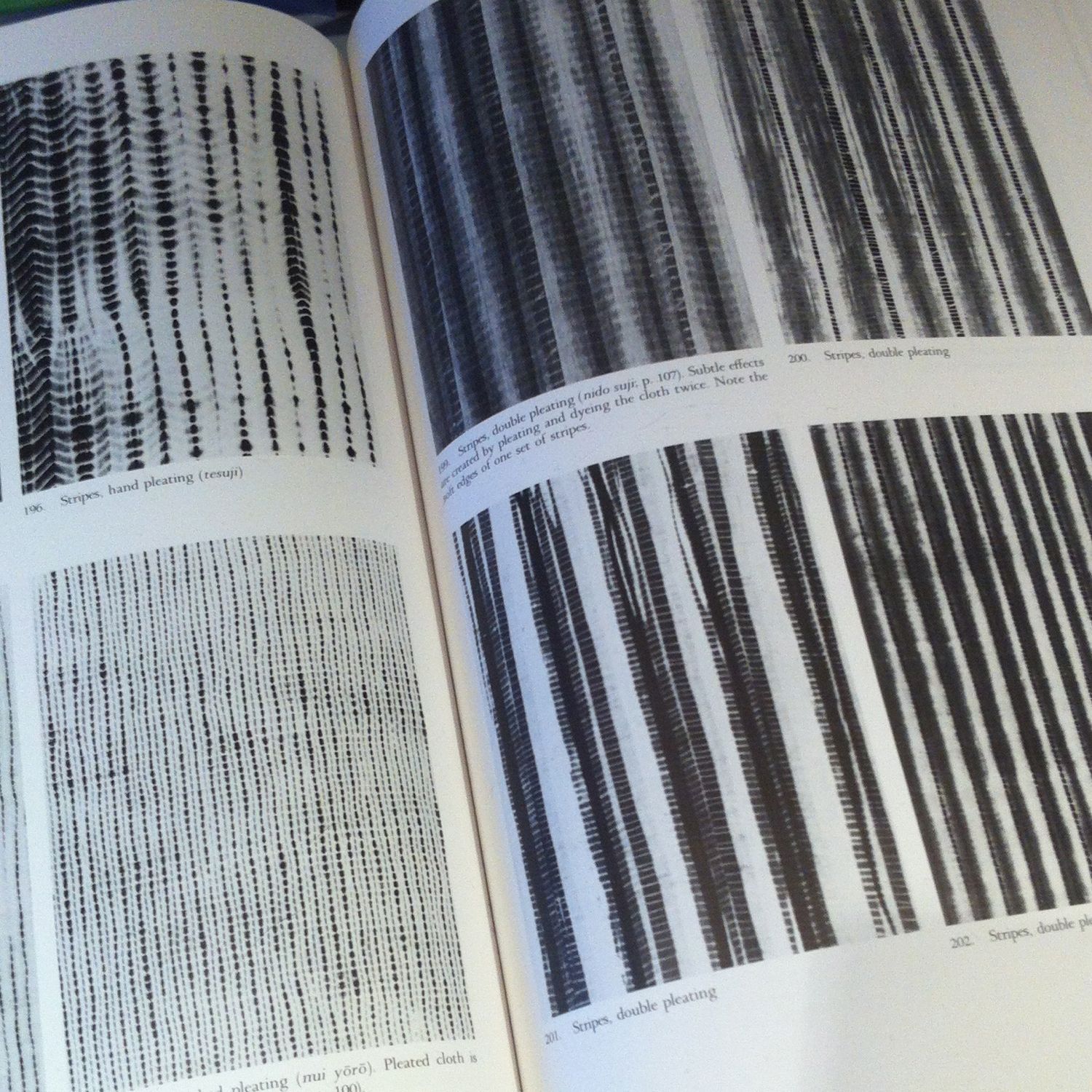

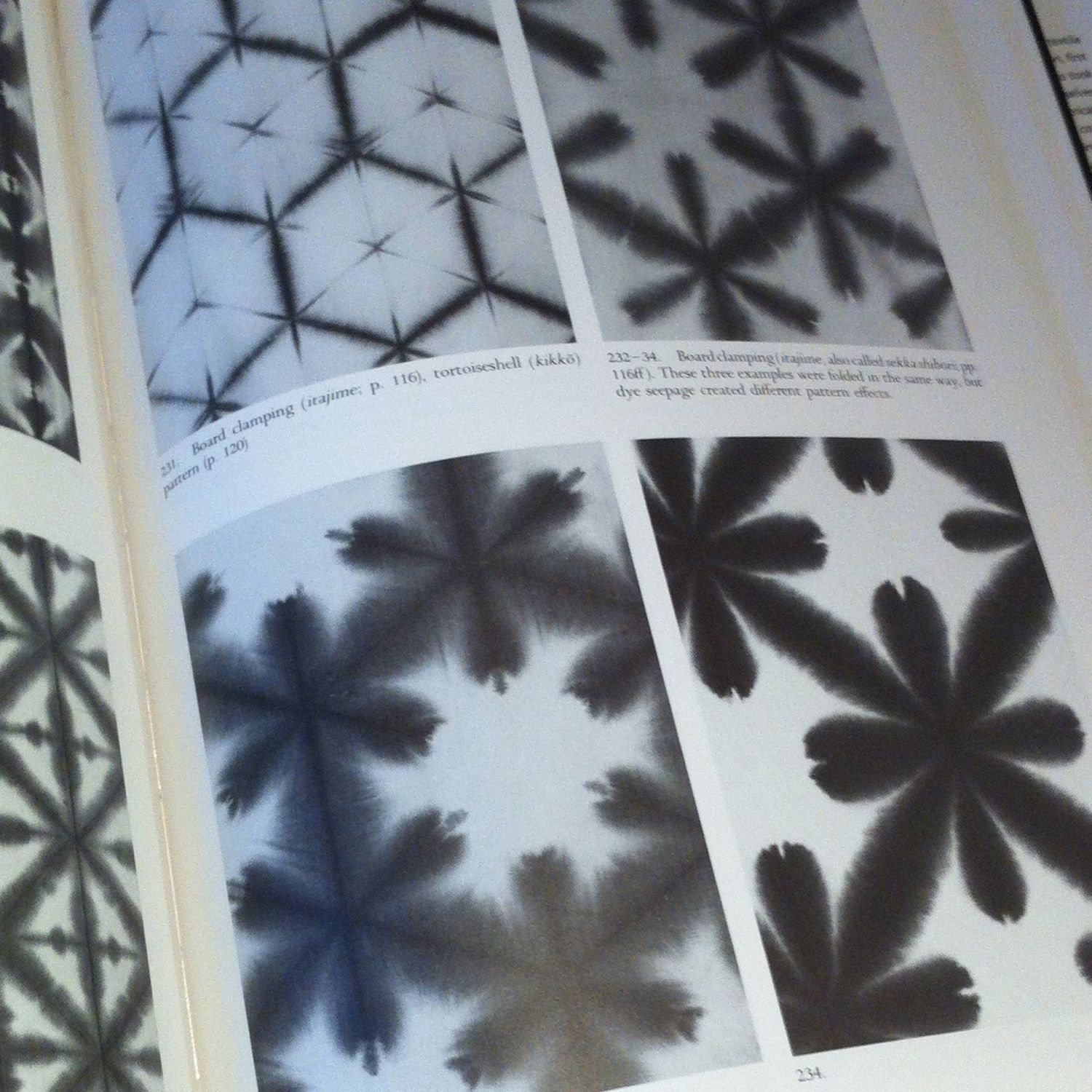

There is no equivalent word for “shibori” in English. The closest description would be “shaped-resist dyeing”. “Tie-dye”, with all its rainbow-dyed-t-shirt associations (in my mind, anyway), doesn’t begin to capture the range and sophistication of techniques covered by the Japanese term. Yoshiko Wada, who wrote two books on the subject, describes over sixty variations and there are certainly more. There are people who have dedicated their life not just to shibori but to just one type of shibori. And there are Western artists who have learned Japanese and studied with Japanese masters to perfect their own interpretations.

Against that background I don’t claim to be a shibori artist. But I do use shibori techniques. Initially I taught myself from Wada’s book, “Shibori: the inventive art of Japanese shaped resist dyeing”. Her instructions are so meticulous that, with patience and lots of experimentation, it wasn’t too difficult to achieve interesting results. Other books and courses (most recently with Jan Myers Newbury, who taught me arashi shibori) and lots more experimentation have developed my understanding.

Images from Yoshiko Wada's book

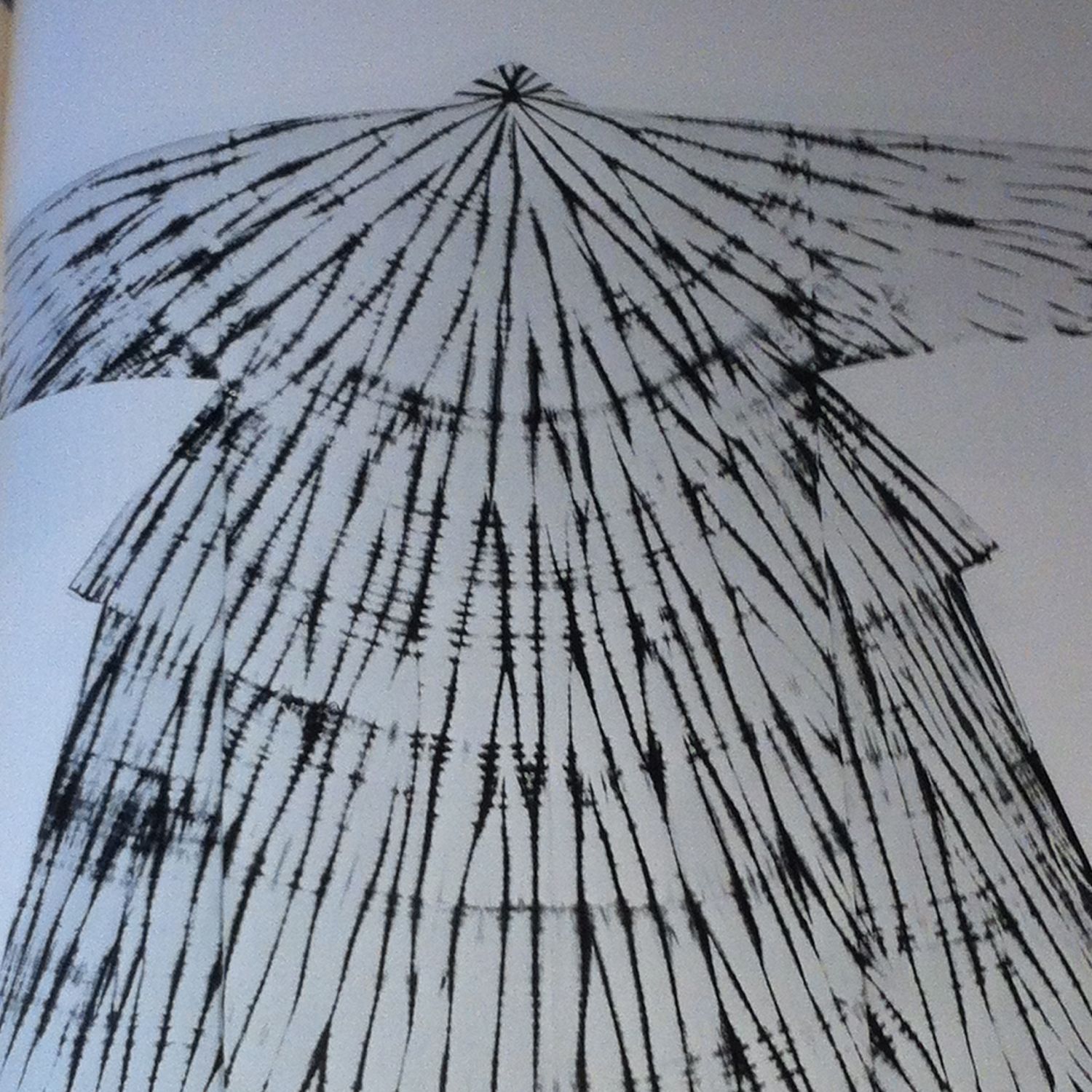

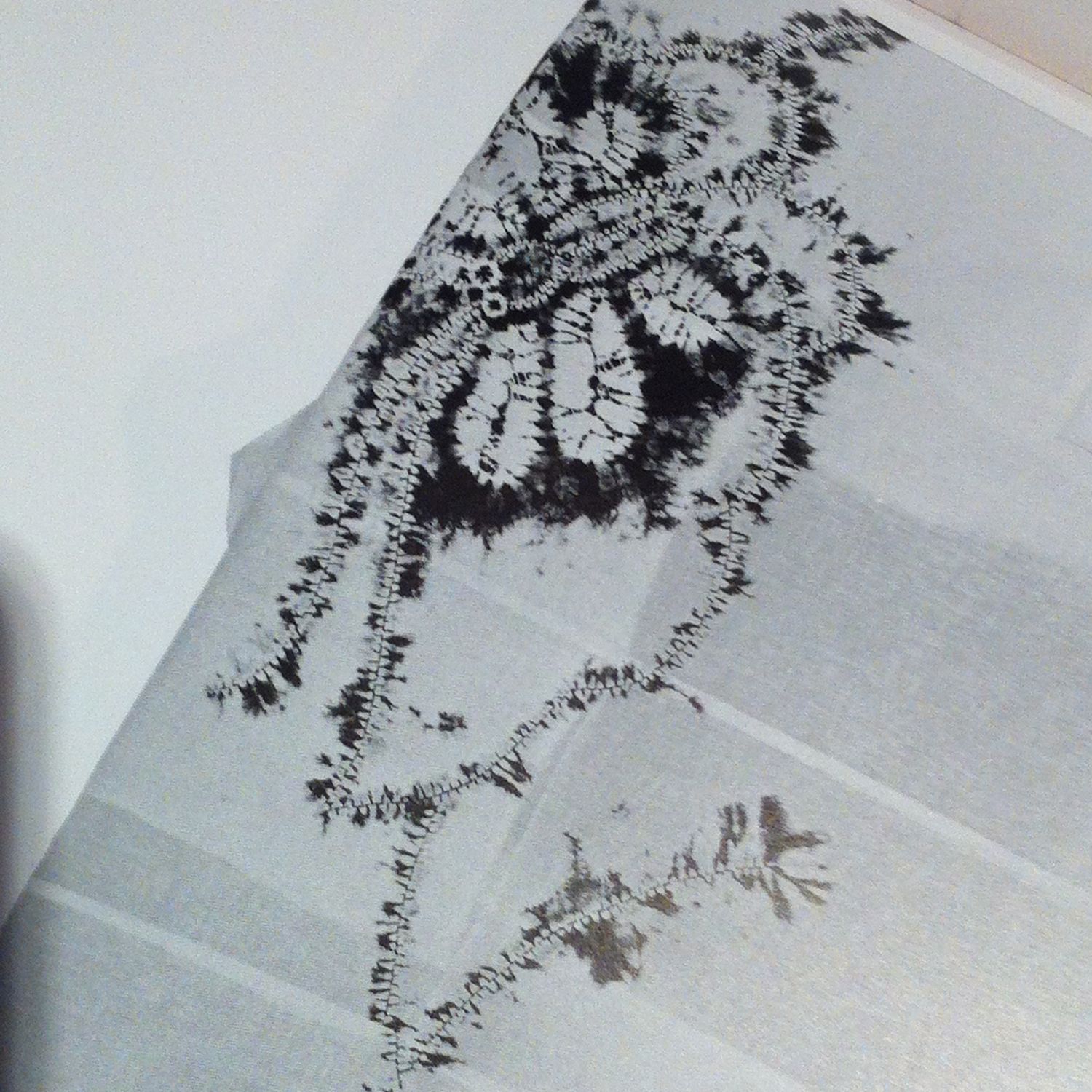

Pleated and stitched resists are the method I like best (see this). Depending how I space the pleats and the stitches I can achieve a range of linear patterns – from fine, straight, parallel lines to wavy, broken ripples. I also use arashi (pole wrap) and itajime (clamp resist) techniques. And shibori lines over cloth that has already been painted or screen-printed with thickened dye add a whole other set of possibilities.

There are shibori techniques that can be done quickly but stitched techniques are usually slow. It takes me 30 to 40 minutes to pleat and stitch a quarter metre of cloth. What makes it worth the trouble, are the characteristic soft edges and organic marks that result. They resemble ripples in the sand, the grain of wood, reflections in the water. The nature of the process means that the dye only reaches the parts of the cloth that are left exposed. So, when you undo it, the marks provide a record of the folds and creases, which mimic the processes that shape and mark surfaces in nature.

Found shibori

It is possible, with experience, to work out how a shibori-dyed cloth must have been folded by studying the marks – “it is the memory of the shape that remains imprinted in the cloth” (Wada). Memory on cloth – with all the metaphorical possibilities that offers.

What I like is that even though I have quite a lot of control over how I manipulate the cloth, in the end I have to let go of the process and allow the cloth and the dye bath to do as they like. I never know exactly what I will get and that’s half the fun. As Wada says, “Chance and accident … give life to the shibori process.”

More about this: World Shibori Network